Museums and art centres, often perceived as places of free expression, are nevertheless influenced by external factors that shape their operation and accessibility.

Access to Culture: Inequalities, Political Issues, and Funding Models

Culture is not just a means of personal fulfilment; it is also marked by structural inequalities. These inequalities manifest themselves in various ways, notably through class relations and funding structures. According to a study by the French Ministry of Culture, a large proportion of public funding in the cultural sector is concentrated in certain regions and institutions, creating disparities in cultural access. In addition, many artistic initiatives are faced with economic pressures that can influence cultural programming, prioritizing mainstream choices over more experimental or marginal projects.

These issues are reflected in a country’s cultural policy, which can be influenced by the prevailing social and political ideology. State investment in arts education and access to culture can promote collective empowerment. For example, in the 1930s, the USSR set up popular art schools that provided working-class children with access to artistic education. However, this initiative was shaped by a strict ideological framework, imposing socialist realism and restricting certain forms of art. In France, under the Popular Front in 1936, measures were taken to make art and culture accessible to the working classes. The introduction of paid holidays enabled workers to travel and visit museums and heritage sites, and support was provided to socially engaged artists, particularly anti-fascists. However, these advances were short-lived and later challenged after the fall of the Popular Front.

Partnerships between public institutions and private companies spark debates about the balance between funding and artistic independence. For example, companies such as LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE) and BMW help fund contemporary art exhibitions, expanding visibility opportunities and making possible projects that otherwise could not have been realized. While these collaborations can enrich the cultural landscape and attract new audiences, they also raise concerns about the commercial pressures they generate, which risk limiting artistic diversity. The pursuit of profitability sometimes leads institutions to prioritize mainstream works at the expense of more experimental or niche creations. As a result, museum curation could be shaped by commercial criteria rather than by a commitment to artistic diversity.

Testimonies from stakeholders in the sector illustrate this ambivalence. For example, in an interview with a cultural media outlet, a museum director emphasised that collaborating with private companies could help maintain a high standard for exhibitions. However, she also mentioned that this created pressure to steer the programming towards more commercial choices. Similarly, an artist who had recently accepted corporate funding for an exhibition pointed out that it is difficult to escape this logic due to limited public resources. The economic pressures exerted on cultural institutions can directly influence the choice of works presented, and some exhibitions may turn towards safer or more popular options, thereby reducing the space given to more experimental art forms. The drive for profitability can also influence artistic approaches, encouraging some artists to conform to commercial expectations rather than pursue free creative expression. This can lead to a restriction in the diversity of artistic forms and narratives presented in public space.

However, these collaborations are not the only answer to the question of cultural funding. Local and alternative initiatives are emerging to offer access to culture without relying on traditional institutional channels. In Italy, for example, the ‘CulturaInMovimento’ programme provides free or reduced-price access to culture for communities in marginalized areas, thus helping to reduce inequalities in access. These projects are often led by artists’ collectives or associations, which aim to create cultural spaces open to all, regardless of social status or ethnic origin. These initiatives illustrate the possibility of proposing alternatives to institutional culture, focusing on inclusiveness and accessibility, without being constrained by the logic of profitability.

Minorities can be particularly affected by cultural inequalities. Access to culture is often more limited for certain groups, such as ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, or LGBTQ+ communities. These groups sometimes face additional barriers to accessing culture, both in terms of availability and representation. Works created by members of these groups may struggle to gain visibility, sometimes being pushed to the margins of major cultural institutions, reinforcing stereotypes and exclusions. The absence of diversity in artistic programming can limit the narratives represented and reduce the plurality of essential voices in the cultural space.

Technology, diversity and inclusion: Reinventing culture for all

In this dynamic, culture remains a powerful tool of resistance. Throughout history, numerous artistic movements have emerged to challenge power relations and give a voice to marginalised groups. From the Harlem Renaissance in the United States to Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed in Brazil, and the cinematic productions from the Global South, art has served as a means of political protest. Today, collectives such as the Mouvement Décolonial in France and Afrofeminist artists use art to challenge systemic discrimination and propose new narratives. Some collectives, like Spain’s La Fura dels Baus, are exploring alternative funding through crowdfunding and self-management to maintain their independence amidst increasing precariousness. While these practices remain fragile, they offer avenues for rethinking culture as an inclusive space, liberated from dominant economic logics.

The development of new technologies and digital tools is altering cultural dynamics. On the one hand, it facilitates greater access to art and creativity through online platforms, virtual museums, and digital distribution initiatives. Many artists now use social networks and crowdfunding platforms to reach a wider audience, bypassing traditional channels. However, this digital democratisation does not fully eliminate inequalities. Access to technology is often influenced by economic and geographical factors, and the algorithms used by platforms can promote content standardisation. Furthermore, the value of digital works remains lower than that of more traditional art forms, limiting the institutional recognition of emerging artists in these new media.

Despite efforts to diversify access to culture, studies show that it is still largely shaped by social and ethnic inequalities. In France, for example, a study by the Observatoire des inégalités reveals that the majority of museum directors come from privileged social classes, which influences the artistic choices and narratives presented. While initiatives such as those from the Musée d’Art Contemporain de l’Île-de-France aim to incorporate cultural diversity into their programming, these efforts remain isolated.

Internationally, countries such as Germany and the Netherlands have implemented public policies aimed at enhancing access to culture. These models include substantial public funding to support artistic creation, especially for emerging artists or those from less privileged backgrounds. These examples provide valuable insights for rethinking policies that support a more inclusive culture, with the goal of making art and culture accessible to everyone, regardless of social, ethnic, or geographical background.

Although museums and cultural institutions are intended to be spaces of openness and freedom, culture continues to be influenced by power dynamics and social prejudices. To ensure that art and culture remain domains of free expression, it is essential to rethink their funding and management by exploring more inclusive and sustainable models. Ensuring equitable access to culture must be a priority, which involves supporting cultural policies that promote access to culture while balancing economic imperatives.

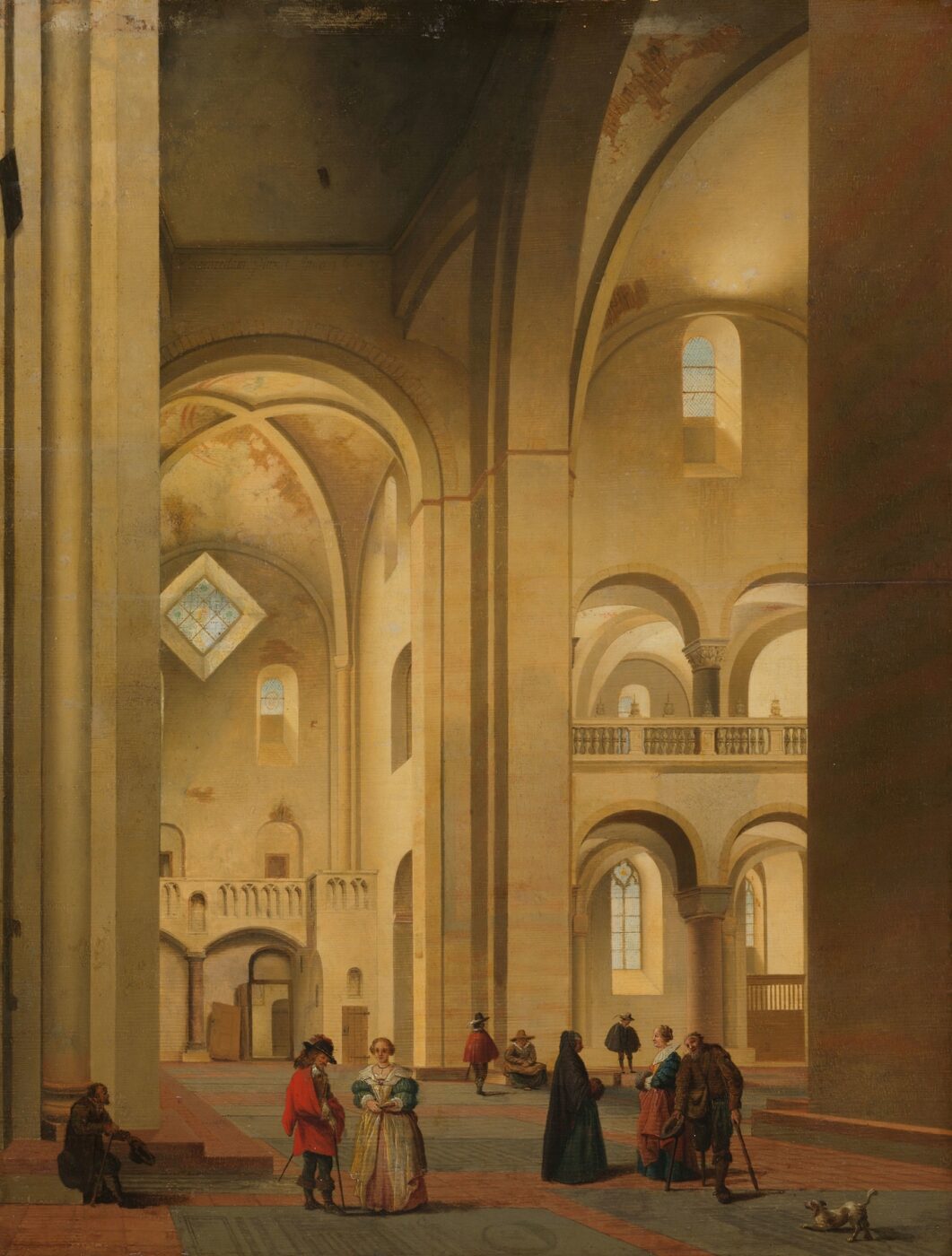

Pictures credit: Eden Lefevre

Featured image: Pieter Janz : The transept of the Mariakerk in Utrecht